Introduction

Extended Reality (XR) is currently one of the most exciting, yet most confusing, sectors in technology. We hear about the “Metaverse” spatial computing, and immersive headsets constantly. But beneath the marketing buzzwords lies a foundation of specific technologies and design principles that define what is currently possible and what the future holds.

To truly understand this space—whether you are a developer, a designer, or a business leader exploring use cases—you need to grasp the mechanics. It’s not just about putting on a headset; it’s about understanding how humans interact with digital space.

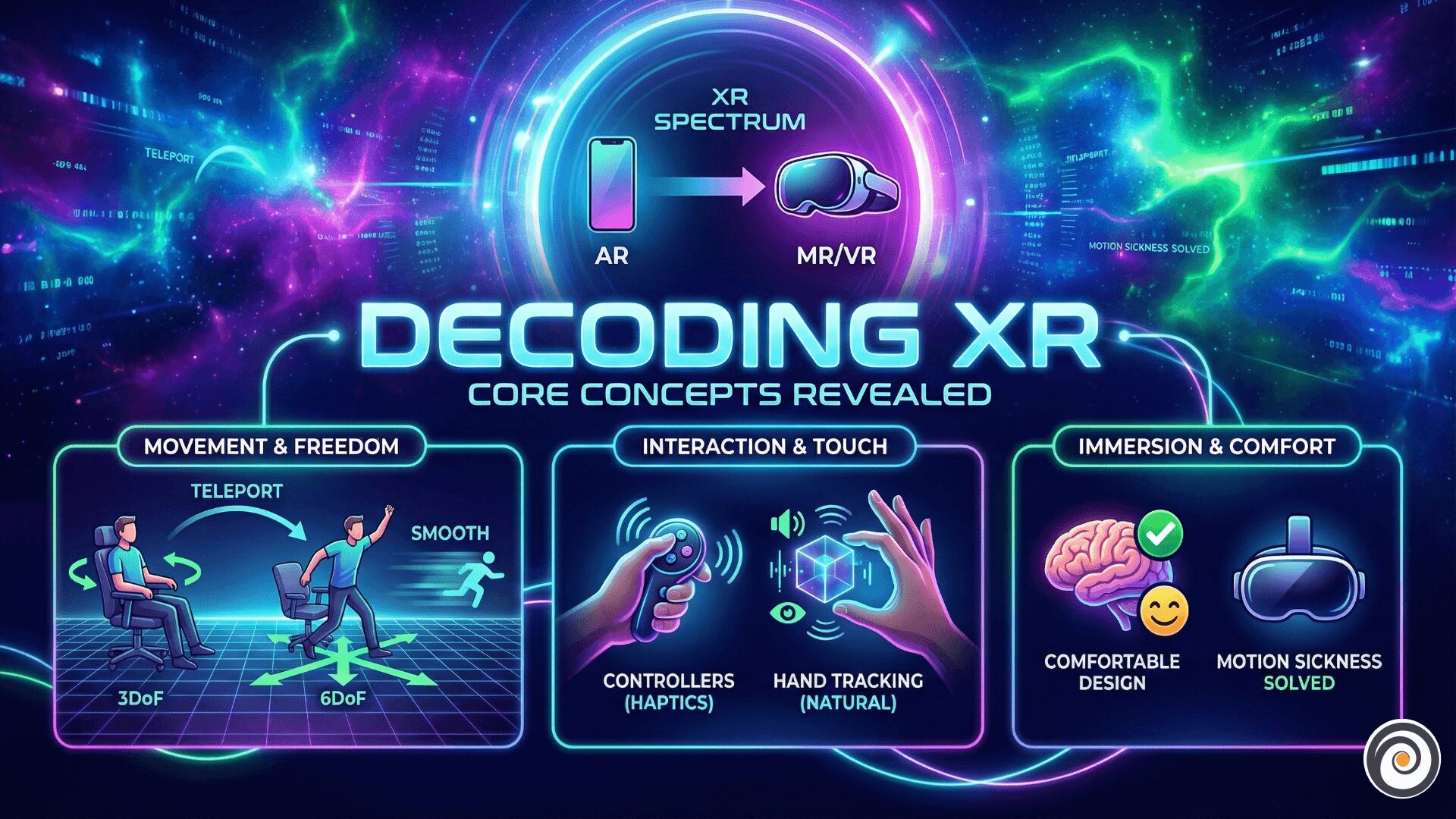

In this post, I want to break down four foundational concepts that govern the XR landscape today: the reality spectrum, degrees of freedom, the challenge of locomotion, and the future of interaction.

1. The Reality Spectrum: AR vs VR vs MR

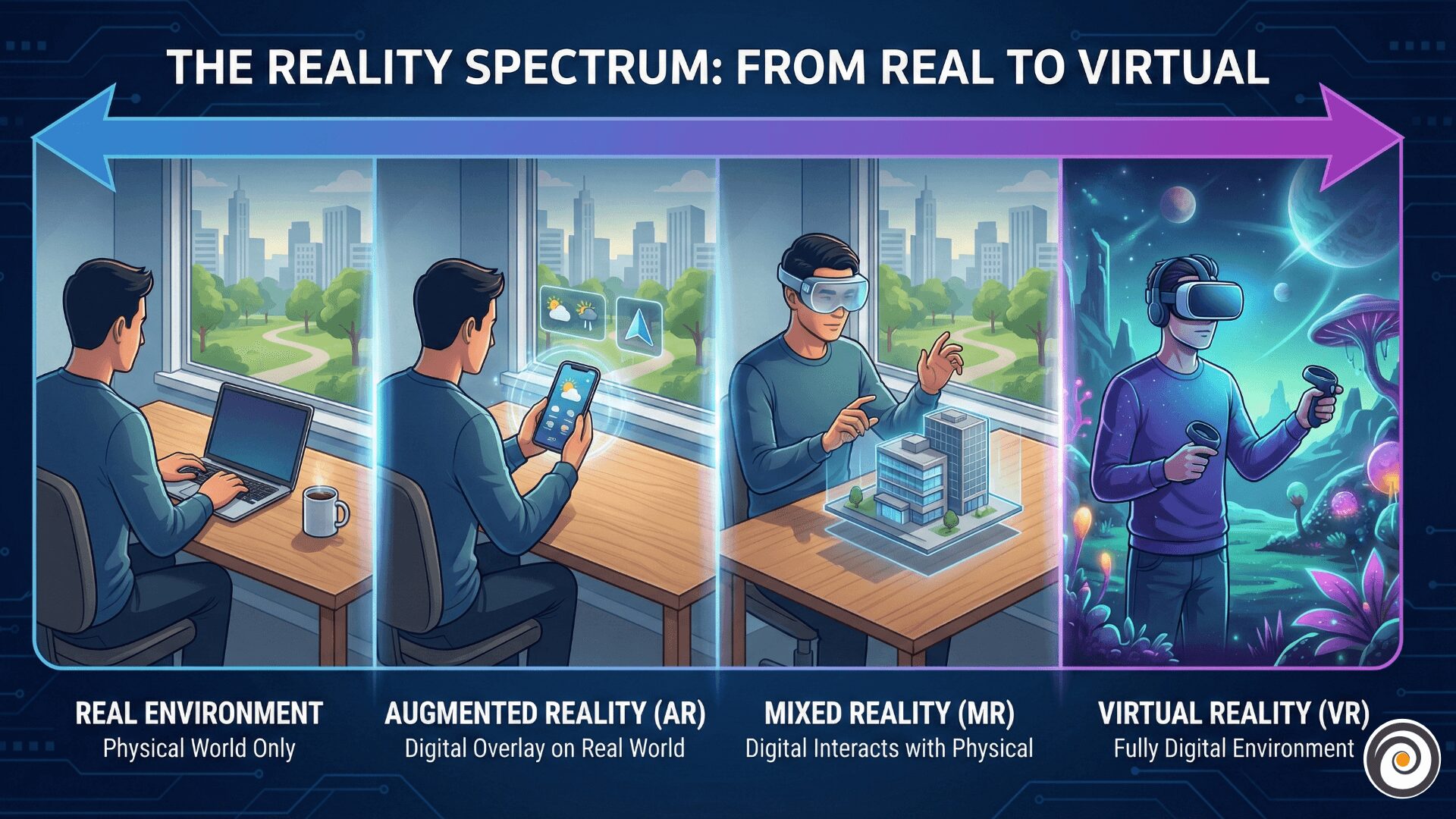

The first stumbling block for many is the alphabet soup of acronyms. “Extended Reality” (XR) is an umbrella term that covers the entire spectrum of immersive technologies.

To understand the differences, think of a sliding scale. On one extreme, you have the real world (where you are right now). On the other extreme, you have a completely digital world.

- Virtual Reality (VR): This is the fully digital extreme. When you put on a VR headset (like a Meta Quest or HTC Vive), you are visually cut off from the real world. Everything you see is synthetically generated. It is total immersion.

- Augmented Reality (AR): This is closer to the real world. AR overlays digital content onto your physical environment. Think Pokemon GO on your phone or simple smart glasses that show notifications. The digital content is there, but it doesn’t necessarily “understand” the physical geometry of the room.

- Mixed Reality (MR): This is the sweet spot in the middle, and often the hardest to define. MR is essentially advanced AR. Not only are digital objects overlaid on the real world, but they can interact with it. A digital ball could bounce off your real-world table, or a virtual character could hide behind your physical sofa. Devices like the Apple Vision Pro or Microsoft HoloLens operate in this space.

2. How We Move: 3DoF vs 6DoF

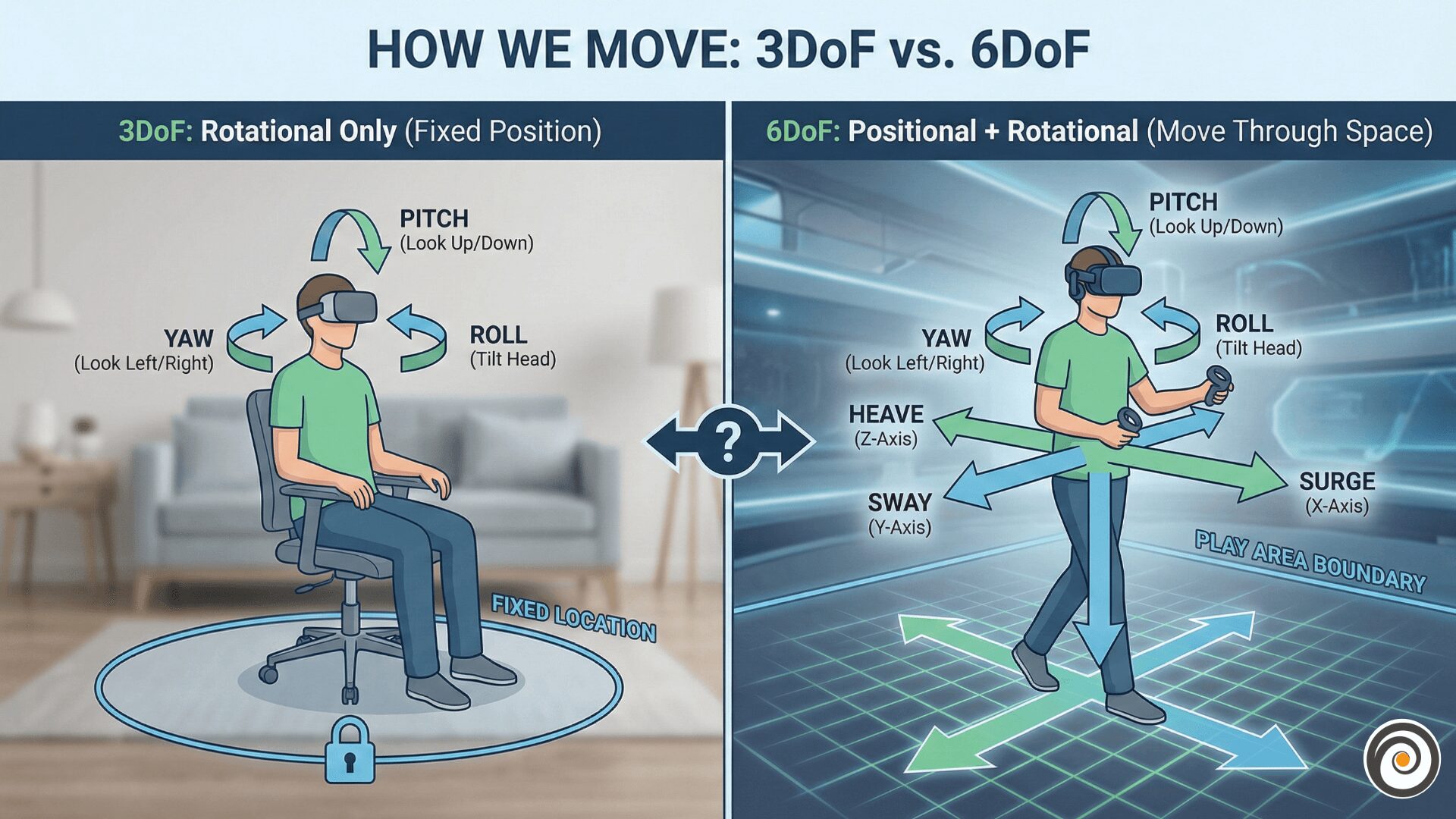

Once you understand the spectrum, the next crucial concept is tracking. How does the system know where you are? This is measured in “Degrees of Freedom” (DoF).

If you’ve ever tried a cheap mobile VR headset five years ago versus a modern high-end device, the difference you felt was likely the difference between 3DoF and 6DoF.

The Simple Analogy: The Office Chair

- 3DoF (Three Degrees of Freedom): Imagine sitting in a swivel office chair that is bolted to the floor. You can look up and down (pitch), look left and right (yaw), and tilt your head side to side (roll). You can look at things, but you cannot move towards them. If you physically lean forward, the virtual world moves with you, which feels unnatural. This is common in older devices or simple 360-video viewing.

- 6DoF (Six Degrees of Freedom): Now, imagine standing up from that chair. You still have the rotational abilities of 3DoF, but now you can also move forward/backward, up/down, and left/right through physical space. If you physically take a step forward, you move forward in the virtual world.

6DoF is essential for true presence—the feeling that you are actually there.

3. The Locomotion Challenge: Solving Motion Sickness

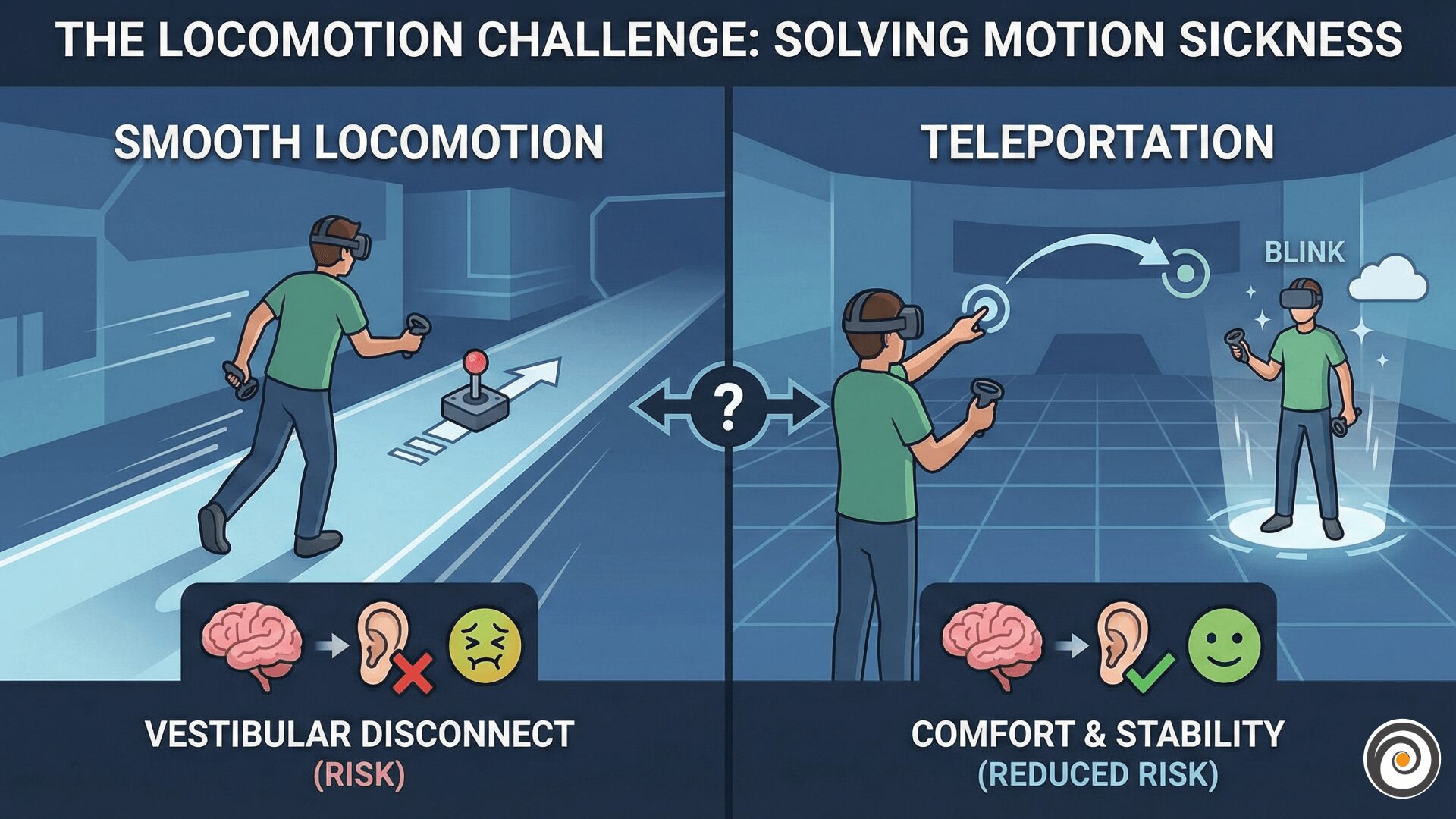

In 6DoF VR, being able to walk around your physical room is great. But what happens when the virtual world is bigger than your physical living room? How do you explore a massive virtual landscape like Skyrim?

This is where locomotion design becomes critical, and it’s a constant battle against human biology.

Motion sickness in VR is basically your brain getting confused. It is exactly like the feeling of reading a book in a moving car or bus. Your eyes tell your brain, We are moving fast inside the game, but your body tells your brain, “We are sitting quietly on the sofa”. This mismatch creates a “disconnect”. Your brain thinks something is wrong with your body—like you ate something bad—so it creates that nauseous (vomit-like) feeling to protect you.”

Developers use two primary methods to solve this:

- Smooth Locomotion: You use a joystick on a controller to glide through the world, similar to a traditional video game. While immersive, this is the most likely method to cause motion sickness in new users.

- Teleportation: You point at a spot in the distance, press a button, and instantly blink to that location. This is highly comfortable because there is no perceived artificial acceleration. However, it can break immersion—you feel less like an adventurer and more like a powerful wizard blinking around the map.

Finding the balance between comfort and immersion is the central challenge of VR level design.

4. Touching the Virtual World: Controllers vs Hand Tracking

Finally, how do we interact with these digital worlds? We are currently at a crossroads between physical hardware and natural input.

![]()

Controllers: Currently, handheld controllers hold the crown for gaming and complex productivity. They offer crucial advantages: precision and, most importantly, haptic feedback. When you pull a trigger to fire a virtual gun or grab a virtual object, the controller vibrates against your palm, grounding the digital action in physical reality.

Hand Tracking: The future, however, is likely controller-free. Using cameras to track your actual hands is incredibly intuitive—it feels like magic to just reach out and grab a digital cube. It removes friction for new users who don’t want to learn complex button maps.

The Design Challenge: The difficulty with hand tracking is the lack of haptics. How do you “feel” when you’ve successfully pressed a virtual button if your finger just passes through thin air? Designers have to rely on clever visual and audio cues to replace the missing sense of touch, creating “buttonless” interfaces based on pinches, gestures, and gazes.

Conclusion

XR is more than just new screens strapping to our faces; it’s a fundamental shift in human-computer interaction. By understanding these core pillars—the spectrum of reality, how we track movement within it, how we navigate virtual spaces comfortably, and how we touch the digital world—we can better evaluate the current tools and design better experiences for the future.

What do you think is the biggest hurdle currently facing mass adoption of XR? Is it the hardware bulk, or is it unsolved design challenges like locomotion? Let me know in the comments.